The Excessive Details—Abridged. Too much information, too little space. A brief history, dictionary, catalog, tourist guide, and essay, on leather.

I will condense the tanning process as much as possible. What is tanning? Well, skin rots. Skin is made of (among other things) keratin. Fingernails are keratin. Fingernails don’t rot. Tanning is the process of removing basically all of the stuff that rots and then modifying what remains, chemically and mechanically, to not rot under most conditions, while remaining both strong and flexible.

This can be done by natural or artificial tanning agents. Natural tanning agents include

Plant tannins, especially from oak, quebracho, and mimosa. Plant tannins produce “vegetable tanned” or “vegtan” leather. This is more or less the oldest and most revered tanning method. Only a small fraction of global leather production is vegtan leather—for instance, to my knowledge, the US and Canada have three major vegtan tanneries combined. All three of them are currently in the US.

Brains, eggs, smoke, urine, and a bunch of other things. I do actually know where to get some braintan and buckskin leathers, though their applications are outside my expertise (more useful for garment making).

“Artificial” tanning agents include chromium, zirconium, and tons of other proprietary mixtures and chemicals, etc. Mostly chromium though. There is a common misunderstanding that chrome-tanned leather is universally inferior to vegtan, is toxic, a sign of poor craftsmanship, etc. This is not really true. Most leather made every year is chrometan, because it takes days or weeks instead of months or years. Like any widely-produced material, you can find chrometan leather that ranges in quality from trash to treasure. Some of the absolute best leathers in the world are chrometans or combination tans, like Chromexcel from Horween or the huge variety of calf and goat leathers from Degermann, Haas, d’Annonay, Alran, and many more.

Leather: Structure and So-called “Grades”

Leather anatomy:

Leather is made of a gradient of fibers. The fibers on the interior side of the leather, the “flesh” side, are larger, individually stronger, but much more loosely connected. The fibers on the exterior side, the “grain” side, are incredibly small and densely packed, making for the almost solid surface we know and love. Most of the strength of a leather hide comes from the grain portion.

Leather “Grades”:

The biggest myth about leather in the general public, I wager, is that there is a consistent grading of leather that goes something like full-grain, top-grain, and “genuine” leather. The reality is significantly more complicated.

Leather is a rather loosely restricted material, commercially—not entirely without good reason, to be fair. All that is required for leather to be “genuine” in general is that it must actually be made from a tanned animal skin. This means that all of the best leather in the world is genuine leather.

Similarly, full-grain leather (as I explain in the next column) simply means that the grain side of the leather has not been sanded to correct flaws. Some of the best leather in the world is full-grain leather, yes, maybe even most of it, but so is some of the worst leather in the world. I can make the most hideous piece of leather you’ve ever seen in my back yard, and as long as I haven’t corrected the grain, it’s full-grain leather.

So, in brief, genuine leather is the broadest term and just means that it is actually leather, regardless of quality. Top- or full-grain only refers to how the grain has or hasn’t been finished, regardless of quality.

Leather “Grade” Terminology:

Full-grain: Leather that has not had any correction done to the grain (exterior) side of the leather.

Top-grain: Leather that has had fairly minimal correction done to the grain side of the leather. Enough to remove surface flaws, but not enough to significantly decrease the strength or texture of the leather.

Corrected-grain: Broader than top-grain, as it includes more significant sanding or correction of the grain side, often in order to produce a suede-like surface (called “nubuck.”)

Suede: Leather that has been split off of the grain side, trimmed, and buffed. Weak, but supple and soft.

Split: Leather that has been split off from the grain side, with little additional treatment. Weak.

Genuine leather: If it’s an actual tanned piece of animal skin, it’s genuine leather. This is often used by unscrupulous brands to refer to very cheap split leather that has been coated with a synthetic finish, like vinyl.

Bonded leather: The particle board of the leather world. Leather scraps, fibers, and fragments, glued together with something like rubber or vinyl. More or less pointless.

So, rapid-fire, here are almost all the specialized leather types (not animal types, necessarily) that I know:

Alum tan/Tawing: Sort of like chrome tanning before chrome tanning was discovered in the 1840s. Tawed leather is a semi-tanned leather, which is quite water-sensitive, but is naturally a very light color and makes for supple fine leathers, like for gloves.

Bridle/harness: Close enough to interchangeable terms for vegetable tanned leathers that have been thoroughly hot-stuffed with oils, fats, and waxes. This makes for a very durable, weather resistant leather with deep color suited for horse tack or just a nice wallet.

Chrometan: Leather tanned with (usually) chromium salts, sometimes other metal salts. Known for colorfastness, ability to take very light/vivid dyes, abrasion resistance, and generally lower cost, all depending on specific tannery and treatment.

Combination tan: Any two or more tanning methods used in conjunction or sequence to impart (hopefully) the best of both worlds.

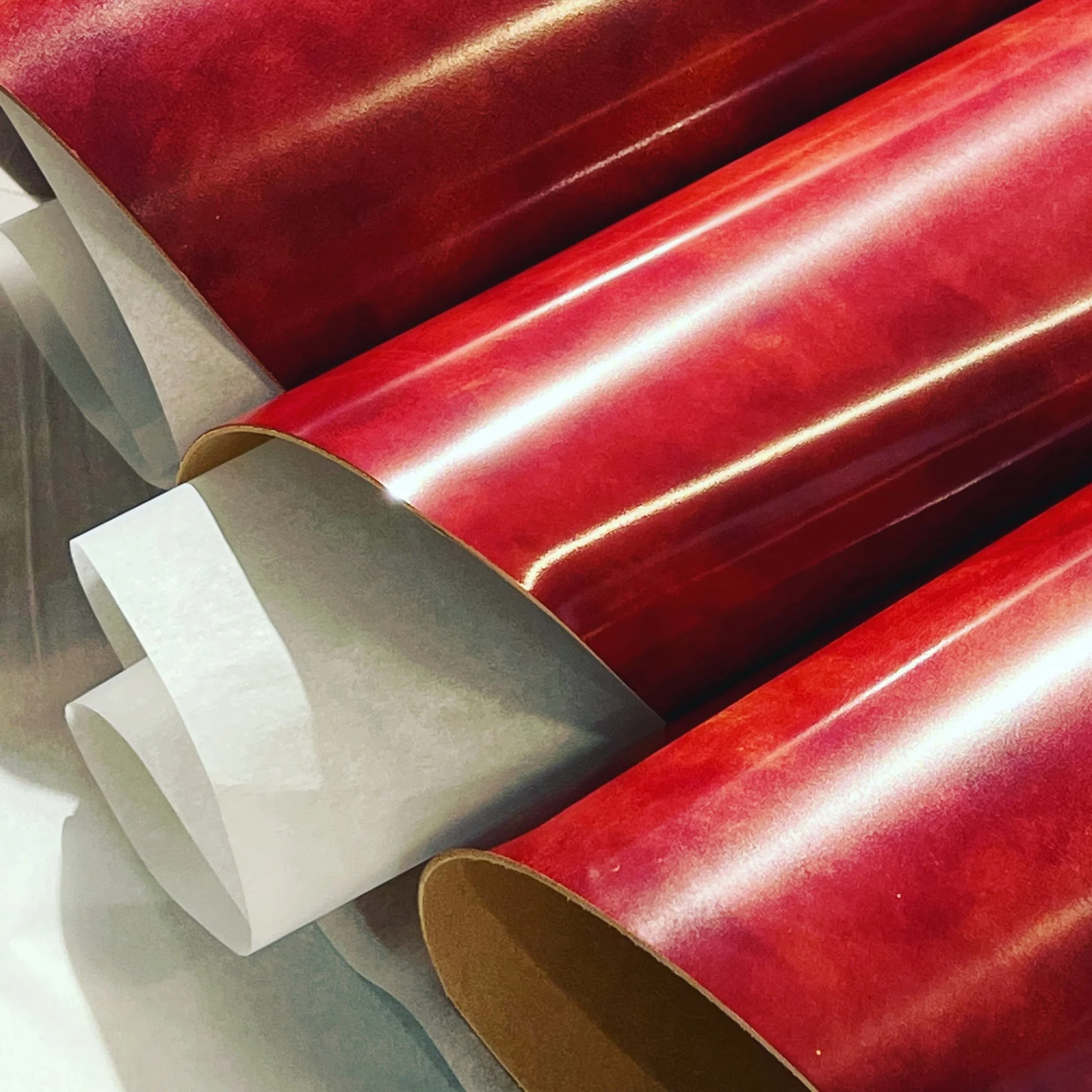

Cordovan: A leather, one of the most expensive and excellent in the world, made from the connective tissue of equine rumps. Only certain large work-horses, mostly European, have a thick enough "corium" to turn into cordovan. The process is one of the longest in the industry, but it produces an incredibly dense, lush, almost iridescent leather that rolls instead of wrinkles.

Latigo: Similar to bridle/harness leather, but combination tanned (nowadays, with chrome/veg; in the past, alum/veg), then hot-stuffed. The primary effect this has is diminishing the stretch of the leather and making it even more durable.

Nubuck: A kind of corrected grain leather where the grain side has been sanded and buffed to create a subtle suede-like surface while removing surface flaws. Often used for footwear.

Oiltan: Historically, I believe oiltan was actually tanned with codfish oil. Now, it is a rather inconsistent term that most often refers to a chrometan leather that has been heavily impregnated with fats and oils to make for a durable and water-resistant leather which has a strong “pull-up” where the color changes when the leather is bent. Sort of a chrometan vachetta.

Rough-out: The flesh side of a leather hide can be sanded and buffed to create a leather that combines the strength of top- or full-grain leather with the softness of suede. It is more resistant to scuffs and hides damage much better. Usually used for footwear, especially boots.

Suede: When leather is split, the portion that doesn’t have the surface grain can be trimmed and brushed to make what we know as suede. While much weaker than top- or full-grain leather, it is affordable, supple, and soft, making it excellent for linings and other low-wear applications.

Vachetta: A broad term for mostly Italian vegtan cowhide leather that has been heavily impregnated with fats and oils, with a fairly natural finish. Known for its soft hand and its patina. Sort of a vegtan version of “oiltan.”

Vegan: Literally just plastic and worse for the environment.

Vegtan: Leather tanned with vegetable tannins, like from oak bark. Known for its patina, comfort, long history, and (in my opinion) still irreplaceable aesthetic appeal.

Hide Categories

I cannot possibly list every kind of animal that has been used to make leather and all the characteristics thereof, considering that cowhide alone has a dozen different categories depending on age, hide part, tannage, treatment, and so on. However, here are the broad strokes of different animal leathers and their applications:

Boar: Made from both boars and sows, leather from adult pigs is known for being both thick and flexible, as well as having an intensely pebbled grain. Highly durable, it is used mostly in saddlery and shoe-making.

Buffalo: Unsurprisingly like cow, except with a looser grain structure and more large-scale texturing like rippling. Suitable for most of the same applications as cowhide, for when you want a more "charactered" look.

Calf: Young cow, which has most of the usual characteristics of cow while being stronger at thinner weights and with generally a tighter and more flawless grain. Excellent for bags, shoe uppers, and small goods.

Cowhide: The standard, due partially to its versatility and partially due to its enormous availability from the global beef industry. Good, if not outstanding, by almost every metric. It is the only widely available hide source thick enough to use for "sole bends" used in shoe-making.

Deer: A loose-grained and supple leather with a lot of character. Good for bags and other "soft" applications.

Fish: (Other than shark and skate). Much like reptiles, mostly used for small, decorative applications, though actually stronger than most leathers at its thickness.

Goat: A pebbled grain. Generally firmer than sheep. Great for gloves, bags, wallet pockets, and other applications that need thin, strong leather.

Horse: Possibly my favorite leather to work with. With a denser, thicker grain than cow and more interesting grain patterns, it dyes and burnishes beautifully, ages incredibly, all while being stronger than most of the competition. Great for most things except when very heavy or very light leather is needed.

Kid & Lamb: Young goat and sheep, which (much like calf) has a lot of the characteristics of the adult animal while being lighter, smoother, and more supple. Most famously used for gloves, but great in any fine and delicate application.

Pig: Known for its very textured grain and raised hair follicles, its most famous application is for American footballs. However, it is also an excellent choice for gloves and other applications that take advantage of its looser grain, durability, and flexibility.

Reptiles: Snakes, crocodilians, lizards, and so on. Most are best suited to low-wear decorative applications, though crocodilian leathers can stand up to decent wear.

Shark: A very durable and wear resistant leather, while not as difficult to work with as skate leather. In addition to the usual small goods, it is used for shoe uppers and bags.

Sheep: A lightly pebbled grain. Supple, while remaining strong at lighter weights. One of the best option for gloves and soft-body bags.

Skate: The hardest, most wear-resistant leather in the world. Its densely-packed, round scales are usually sanded down to produce a glassy finish and can barely be worked with normal tools. Best used for watch straps, bands, and wallet exteriors.